|

||

Best viewed in

|

For centuries the MacNeil clan based on the Hebridean island of Barra have proudly claimed to be descendants of Ireland's "greatest" King, Niall of the Nine Hostages a king of Tara in Ireland who ruled around 400. But a check on hundreds of modern day MacNeils has revealed their roots actually lie with the Vikings and not the Irish. DNA swabs taken from Barra MacNeils as far away as Canada and Australia have proved that the blood of fierce Norse raiders runs through their veins. The finding comes from the MacNeil Surname Y-DNA project run by genealogists Vincent MacNeil and Alex Buchanan. Clansmen from all over the world including Scotland, the US, Canada, New Zealand and Australia have provided DNA samples. MacNeil remains the main surname on Barra on the southern tip of the Outer Hebrides with a population of just 1,000. Clansmen believed they descended from Niall of the Nine Hostages through an 11th century Irish prince who immigrated to Scotland. But the DNA project has not found a single match to Ireland. The name is derived from Niall. The first Niall came to Barra around 1049 and is considered to be the first chief of the clan. Neil MacNeil was the fifth chief and was described as a prince at the Council of the Isles held in 1252. He was still chief after the Battle of Largs in 1263 which ended the domination of the Western Isles by the Vikings from Norway. Neil's son, Neil Og Macneil, is believed to have fought for Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn in 1314 and was given land in northern Kintyre. Gilleonan, the 9th chief, was given a charter of Barra and Boisdale in 1427 from the Lord of the Isles. In the 16th century, the 12th chief (also named Gilleonan) attended a meeting with King James V at Portree, along with a number of other island lords. He was promptly imprisoned for many years, despite being promised a safe conduct by the king. He was not released until 1542 when the Regent Moray tried to use the chiefs in the isles to inhibit the power of the Campbells in Argyll. In the 16th century, the MacNeils augmented their income with a bit of piracy and were sometimes referred to as the "last of the Vikings". The 15th chief was denounced so many times that he was labelled a "hereditary outlaw". On one occasion the chief was tricked into appearing before King James VI for attacking the English ships of Queen Elizabeth. When asked why he had done so, he replied that he thought he was doing the King a favor by annoying the woman who had beheaded the monarch's mother (Mary Queen of Scots). Eventually, the king issued letters requiring loyal subjects to "extirpate and root out" both the chief and members of the clan. In 1610, the chief's nephews attacked the seat of the clan chief at Kisimul Castle, captured their uncle and put him in chains. The chief's son became head of the clan and fought for King Charles II at the Battle of Worcester. The next chief, Roderick Dhu, was received at court in London and granted a royal charter for all the lands of Barra. The clan remained loyal to the crown - including the "Old Pretender" when the Jacobite Uprising of 1715 took place.

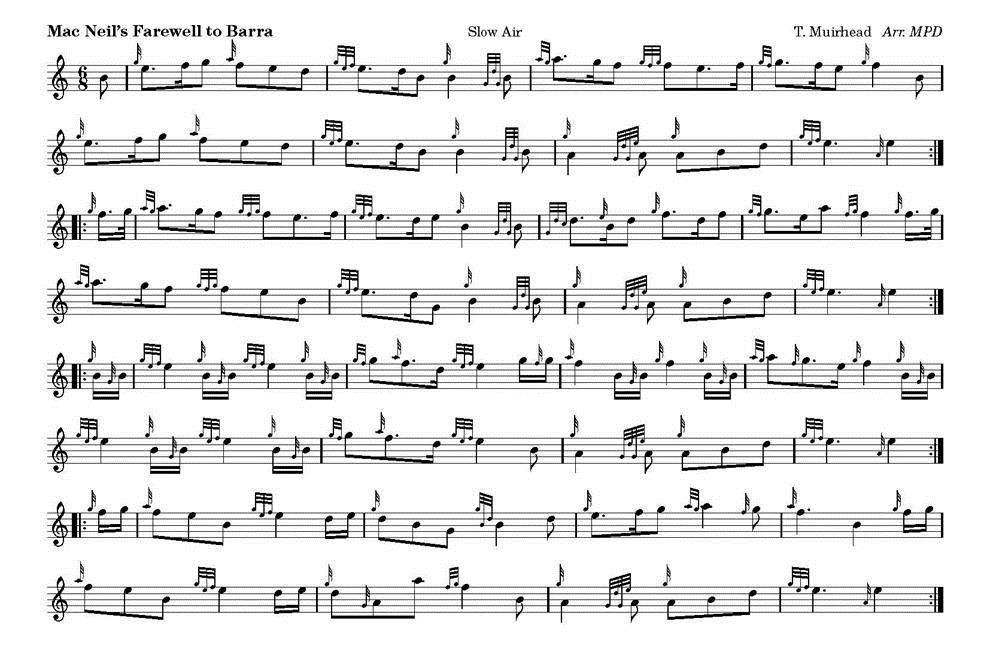

The MacNeil stronghold on Barra was Kisimul Castle. There may have been a building there as early as the 11th century but the present structure probably dates from the 13th century but the dates are uncertain. The castle was besieged several times in the various clan wars. But when the 21st clan chief became bankrupt in 1848, it was sold along with Barra to the Gordons of Cluny who later sold it to the Cathcarts. The line of the hereditary chief passed to a cousin who had immigrated to North America earlier in the 19th century. In a romantic turnaround, a later clan chief, Robert Lister MacNeil, came back from America to Barra in 1937 and purchased the castle and subsequently devoted his life to restoring it. His son, Ian Roderick MacNeil (the 46th of the Clan MacNeil if you start with Niall of the Nine Hostages) is a distinguished lawyer and has continued that task. Recently the National Trust has taken over the restoration work on a long-term lease (for a Pound a year and a bottle of whisky!) The tune, MacNeil’s Farewell to Bara, was written by T. Muirhead. Tom Muirhead – usually known as ‘Tam’ – was born at Meadowfield Row, Longriggend, Lanarkshire on October 27, 1900. His parents were William Muirhead (b.1868), a coal miner, and Mary Whitelaw (b.1869) Artistic interests featured from an early age in Tom’s life. By age six he was being encouraged to go to his bedroom and practice the accordion. His older brother James played, so there was already an accordion in the house. He never had lessons from a teacher. He learned everything by ear and only later came to read music. As a teenager he would play at dances and weddings all over the district, and by the age of seventeen had bought a motorbike so he could get to outlying village halls. Special straps held the accordion on his back while he rode the motorbike to gigs.

Tom left school by age 13 to work in the coal pits. Years later, in the 1930s, he would nearly lose a hand in a mining accident, and this steered him back toward surface work as chief plate layer on the Southfield Colliery railway, where he remained for the rest of his working life. During the miners’ strike of 1926, he was keen to do what he could for the relief effort, playing accordion on the sands in Ayr and Troon, sharing his earnings amongst the miners. At this time, he was also part of a traveling group performing in halls in Glasgow. The troupe included singer J.M. Hamilton and Nellie Wallace, another acclaimed singer of the day. During the war years, he often went around the town on flatbed lorries, playing with groups who were collecting for charity, as charity work was a particular passion. He also played for the Highland Dancers at Gala days in the area. He played the four-row Italian style accordion over the usual three- or five-row style usually favored in Scotland at the time, believing it to have much more versatility in fingering than the more popular models. In 1924 he bought a Ranco Guglielmo four-row, button-keyed accordion direct from Italy. He looked at instruments in an Italian catalogue, and, with translating help from Freddie Valerio, the local Italian ice-cream seller, he ordered what he wanted from the Italian music dealer.He had heard pipes from earliest times, as he had some cousins who played. One of them, Eileen Wilson (pronounced Eelen), was a fine player and won many prizes but was rather frowned upon by men pipers of the time who felt women shouldn’t be competing. Two other male cousins were also pipers. In the 1940s, Tom started up a band with Jock Conner on second accordion and Benny Cartie on drums. The band lasted for some years, and Tom’s business card at the time read Tommy Muirhead, Ace Accordionist, 5 Stane Place, Shotts. Posters promoted Tommy as a premier accordionist. Of course, musical pursuits, had to fit in with the ongoing grind of daily working life. On a typical day, Tom would return from work at 4.30 pm, wash, and if playing that night, would have a couple of hours sleep, get up, dress and head off to the evening engagement. He would routinely play dance music on the accordion for three hours at a stretch, having worked all day. He had a close association with the Shotts and Dykehead Caledonia Pipe Band, and especially with the McAllister family, who lead the band for several generations through the mid-1900s. Tom McAllister, Jr. lived just round the corner from the Muirhead house and Tom was a frequent visitor to the McAllister household to play and listen to music. His ties to this band continued throughout his life. It was through the McAllisters that the tunes of ‘T. Muirhead’ found their way into bagpipe music books and pipe bands. Despite his love of the continental sounds of the Italian style accordion, and his love of music from all over the world, Tom never traveled outside of the British Isles. The Ranco Guglielmo accordion he bought in 1962, is played still today, by his grandson Jim Macfarlane, who delights his congregation by playing it at the Christmas Eve service in Lochgoilhead every year. Tom’s repertoire included tunes from the classics: “William Tell,” “The Barber of Seville,” “Carmen.” He had sheet music sent monthly from London Music publishers Chappel and Matthews. Such pieces as ‘In a Persian Market’ would arrive in the post and Tom would waste no time in trying out these new pieces and asking the family what they thought. He had a trunk full of music, much of it pipe music. He would play away for hours in his room, and it was common to see a group of miners making their way along the road stop near Tom’s window to listen to the strains of his accordion. He took his accordion with him whenever he traveled. One such occasion was a trip from the Broomielaw in Glasgow, to Dublin, when he played on the boat, as the sun set. He often played pipe-like embellishments. His daughter Jessie remembers that he kept a chanter in his drawer in the house and on occasion used to rig up a connection with his accordion, so he could finger while the accordion acted as a bellows. He had a great fondness as well for the Northumbrian smallpipes and tried to imitate their sweet sound on his accordion.Tom Muirhead died on 6th January, 1979, and was buried on January 8th in Stane Cemetery, Shotts. Two pipers from the McAllister family met the cortege at the gates and piped the mourners to the graveside. They played some of his own music, followed by “My Home” and Rossini’s “The Green Hills of Tyrol.”

|

|