Major-General Sir Hector Archibald MacDonald (shown above), also known as Fighting Mac (4 March 1853–25 March 1903), was a distinguished Victorian soldier.

Hector MacDonald was born on a farm at Rootfield, near Dingwall, Ross-shire, Scotland. He was, as were most people in the area at the time, a Gaelic speaker and in later life went by the name Eachann nan Cath "Eachann of the Battles". His father, William MacDonald, was a crofter and a stonemason. His mother was Ann Boyd, the daughter of John Boyd of Killiechoilum and Cradlehall, near Inverness. Hector's brothers were the Rev. William MacDonald Jr., known as 'Preaching Mac', Donald, John, and Ewen. At the age of 15, MacDonald was apprenticed to a draper in Dingwall and then moved on to the Royal Clan Tartan and Tweed Warehouse in Inverness, an establishment owned by a Mr. William Mackay.

On 7 March 1870 Macdonald joined the Inverness-shire Highland Rifle Volunteers, and in 1871 enlisted in the 92nd Gordon Highlanders at Fort George. He rose rapidly through the noncommissioned ranks, and had already been a Color Sergeant for some years when his distinguished conduct in the presence of the enemy during the Second Afghan War led to his being commissioned in his regiment, an extremely rare honour (7 January 1880).

He served as a subaltern in the First Boer War (1880–81), and at the Battle of Majuba Hill, where he was made prisoner, his bravery was so conspicuous that General Joubert gave him back his sword. In 1885 he served under Sir Evelyn Wood in the reorganization of the Egyptian army, and took part in the Nile Expedition of that year. In 1888 he became a regimental captain in the British service, but continued to serve in the Egyptian army, concentrating on training Sudanese troops. In 1889 he received the DSO for his conduct at the Battle of Toski and in 1891, after the action at Tokar, he was promoted substantive major.

During the Mahdist War Macdonald commanded a brigade of the Egyptian army in the Dongola Expedition (1896), and subsequently distinguished himself at the Battle of Abu Hamed (7 August 1897) and the Battle of Atbara (8 April 1898).At the Battle of Omdurman (2 September 1898) the British commander, Lord Kitchener, unwittingly exposed his flanks to the Dervish (i.e., Mahdist) army. Macdonald swung his men by companies in an arc as the Dervishes charged and by skillful maneuvering held his ground until Kitchener could redeploy his brigades. When the fight was over Macdonald’s troops had an average of only two rounds left per man.

After Omdurman MacDonald became a household name in Britain. He was promoted to colonel in the British Army, appointed an aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria, and received the thanks of Parliament and a cash award. His fame was especially high in his native Scotland: on the 12th May that year, described as "one of the heroes of Omdurman," he was entertained to luncheon by the council of the City of Edinburgh, and many Scots felt that Macdonald, and not Kitchener, was the true hero.

In December 1899 Macdonald was sent to South Africa to command the Highland Brigade, under Lord Roberts and Kitchener, Roberts' Chief of Staff, taking part in the Paardeberg, Bloemfontein and Pretoria operations, and in 1901 was knighted as a KCB for his services.

In 1902, following a short period commanding the South District Army in India, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of British troops in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

"Ceylon furnished Macdonald with a lethal combination of a military command which was inactive and uninteresting, and a community of boys who were interesting and very active." He ruffled the feathers of the civilians by forcing the unkempt and ill-disciplined British troops, most of them the sons of British planters, to show more spit and polish; he deeply offended the Governor, Sir Joseph West Ridgeway, when he yelled at him to get off the parade ground; and compounded the process of alienation by declining the social invitations of the British community and consorting instead with the locals. Rumors began circulating that he was having a sexual relationship with the two teenage sons of a Burgher named De Saram, and that he was patronizing a "dubious club" attended by British and Sinhalese youths. Matters came to a crisis when a tea-planter informed Ridgeway that he had surprised Sir Hector in a railway carriage with four Sinhalese boys; further allegations followed from other prominent members of the colonial establishment, with the threat of even more to come, involving up to seventy witnesses. Ridgeway advised Macdonald to return to London, his main concern being to avoid a massive scandal: "Some, indeed most, of his victims ... are the sons of the best-known men in the Colony, English and native", he wrote, noting that he had persuaded the local press to keep quiet in hopes that "no more mud" would be stirred up.

In London Macdonald "was probably told by the king that the best thing he could do was to shoot himself";Lord Roberts, now Chief of the Imperial General Staff, advised him to go back to Ceylon and face a court martial to clear his name. (There was no question of a criminal trial as Macdonald's alleged offense was not illegal in Ceylon). Macdonald left London for Ceylon. Meanwhile Ridgeway, coming under increasing pressure in the Legislature, revealed that "serious charges" had been laid and that the General was returning to a court martial. Macdonald, reading this in the morning newspaper over breakfast in his hotel in Paris, returned to his room and shot himself.

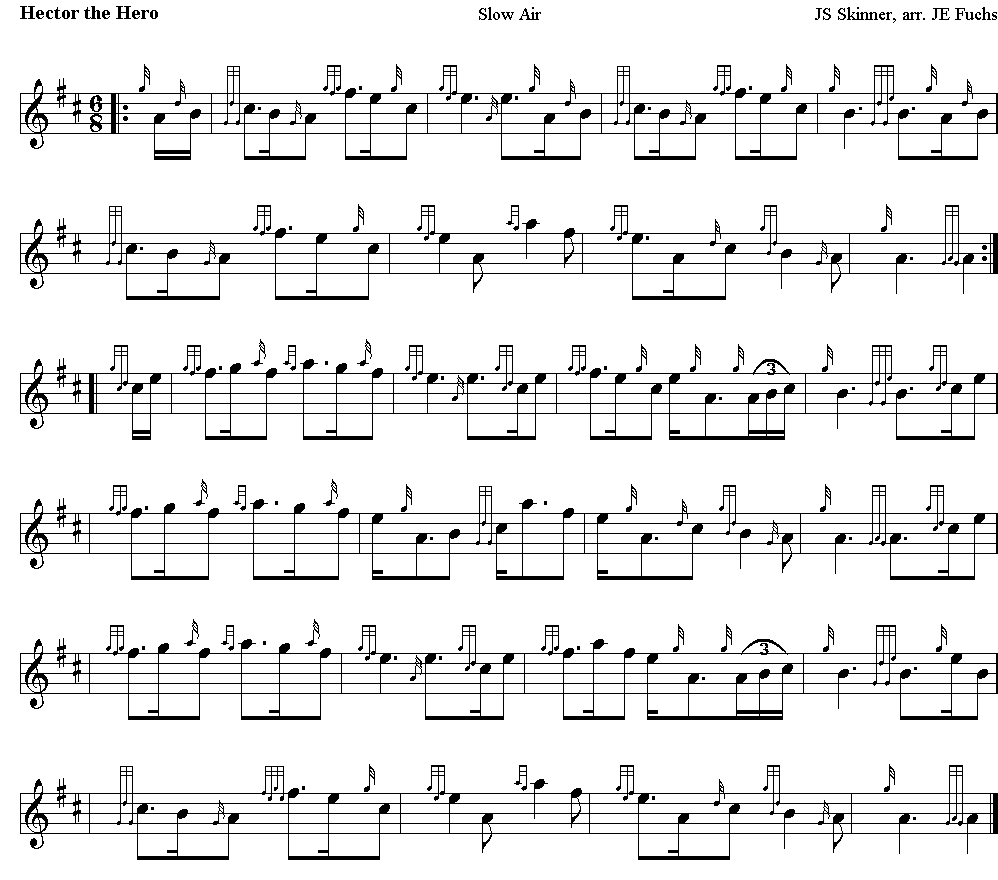

The suicide of the famous war-hero caused great public shock. James Scott Skinner wrote the tune in his honor called Hector the Hero.

James Scott Skinner (August 5, 1843 - March 17, 1927) was a Scottish dancing master, violinist and fiddler. Skinner was born in Banchory, near Aberdeen. His father was a dancing master on Deeside. James was only eighteen months old when his father died. When James was seven, his elder brother, Sandy, gave him lessons in violin and cello. Soon the pair of them were playing at local dances. In 1852 he attended Connell's School in Princes Street, Aberdeen.

Three years later he left to joined "Dr Mark's Little Men", a travelling orchestra. This involved spending six years intensive training at their headquarters in Manchester. It also involved touring round the UK. The orchestra gave a command performance before Queen Victoria at Buckingham on February 10, 1858. JSS attributed his own later success to meeting Charles Rougier in Manchester, who taught him to play Beethoven and other classical masters. Finally he took a year's dancing tuition from William Scott. JSS could now earn his living as a dancing master for the district around Aberdeen.

In 1862 he won a sword-dance competition in Ireland. The following year he won a strathspey and reel competition in Inverness. Gradually he broadened his district of clients until Queen Victoria learned of his reputation. She requested him to teach calisthenics and dancing to the royal household at Balmoral. In 1868 he had 125 pupils there. In the same year his first collection of compositions was published. By 1870 he had married and was soon living in Elgin. For twelve years he continued as a dancing master and violinist. He gave virtuoso concerts, with his adopted daughter joining him as a pianist. In 1881 his wife became seriously ill and died a couple of years later. For the ten years he spend little time in any one place. The 1880s did see three more collections of tunes published. In 1893 he toured the USA with Willie MacLennan, the celebrated bagpiper and dancer.

After returning to Scotland he virtually gave up dancing and concentrated on the fiddle. In 1897 he re-married and wrote some of his best work. In 1899 he made his first cylinder recordings. In 1903, he wrote Hector the Hero, for his friend Sir Hector Archibald MacDonald.